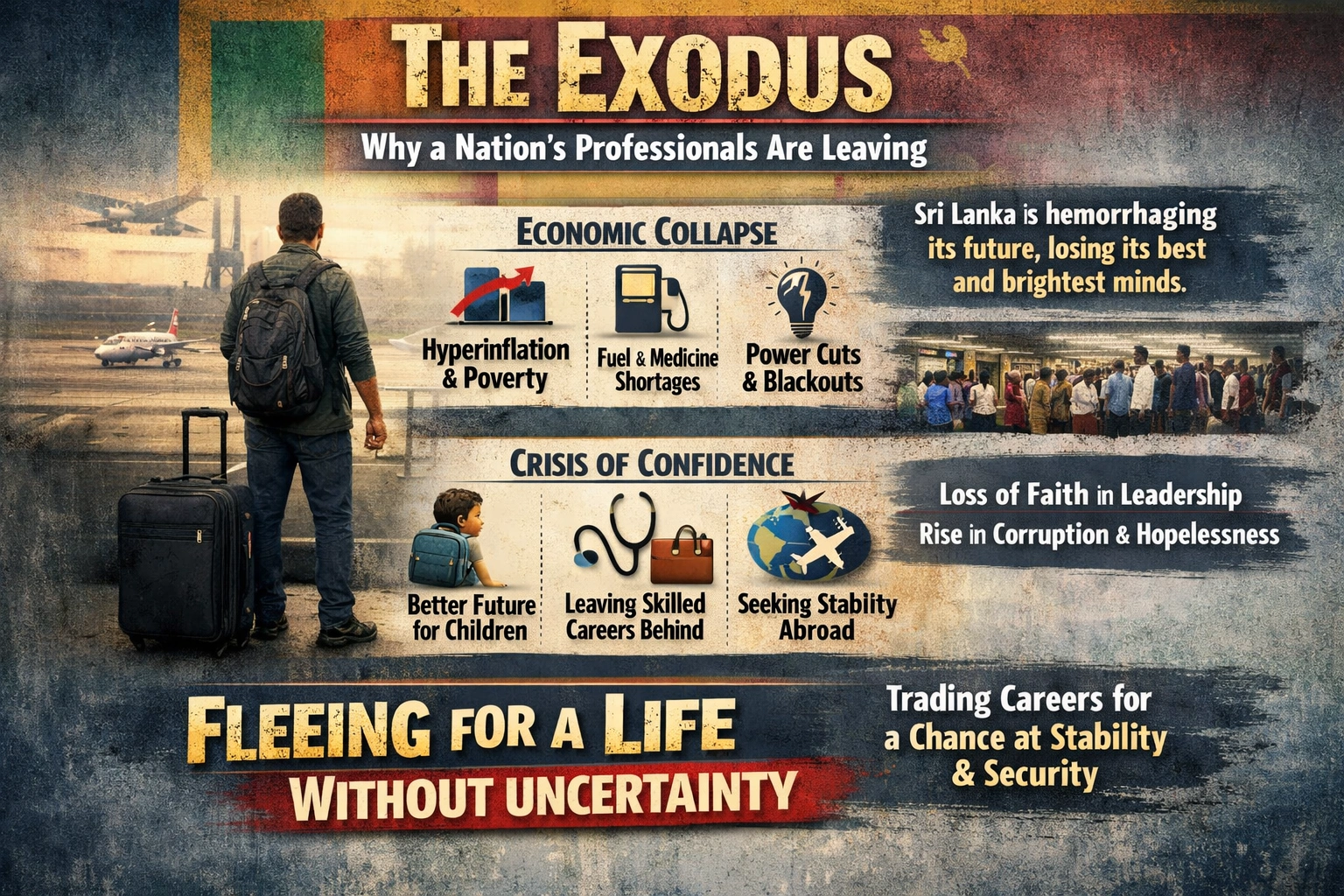

The Exodus: Why a Nation’s Professionals Are Leaving

Sri Lanka is not just losing its people; it is hemorrhaging its future. The recent wave of migration is an exodus of its most skilled minds—doctors, engineers, academics, and IT specialists. They are not merely seeking better opportunities; they are fleeing a future that has become untenable at home.

The primary driver is the nation’s catastrophic economic collapse. Hyperinflation has rendered professional salaries and lifelong savings worthless overnight. Crippling shortages of fuel, medicine, and electricity have paralyzed daily life and professional practice. For a surgeon unable to reliably get to the hospital or an IT manager facing constant power cuts, continuing their work has become an impossible struggle against a failing system.

Beyond the empty shelves and long queues lies a deeper crisis of confidence. A profound loss of faith in political leadership and systemic corruption has fueled a sense of hopelessness. The belief that the country can be steered back on course has eroded, replaced by a desperate need for stability and predictability—qualities that have all but vanished from the island.

Ultimately, the decision is deeply personal. It’s made for the sake of their children’s future, for access to consistent education and healthcare, and for the simple dignity of a life free from constant uncertainty. Professionals are trading their stethoscopes and blueprints for steering wheels and delivery bags, not out of choice, but out of necessity. This exodus is a desperate search for a stable foundation, even if it means leaving their hard-earned careers behind.

From Scalpels to Steering Wheels: The New Reality Abroad

The transition is often abrupt and jarring. In Colombo, they were architects designing buildings, lawyers arguing cases, and surgeons holding lives in their hands. Today, in cities from Melbourne to Dubai, many are behind the wheels of ride-shares, stocking supermarket shelves, or delivering meals. This isn’t a career change; it’s a survival strategy. Fleeing hyperinflation and a collapsing economy, Sri Lanka’s brightest minds have been forced to trade professional prestige for the simple promise of a stable paycheque, sending desperately needed remittances back to families facing shortages of food, fuel, and medicine.

The psychological weight of this reality is immense. It is a daily confrontation with a life unlived and a career abandoned. For many, the loss of professional identity is the heaviest burden. An engineer with a decade of experience feels the sting of being an entry-level worker, their expertise rendered invisible by a new context. Conversations with family back home are often a careful dance, glossing over the manual labour and focusing on the financial stability it provides, masking the quiet grief for a lost status.

This downskilling is rarely a choice. Upon arrival, professionals face a wall of bureaucratic hurdles. Their Sri Lankan qualifications are often not recognized, and the path to recertification is a labyrinth of expensive exams, lengthy courses, and stringent language requirements that can take years to navigate. With families to support immediately, the luxury of time is one they cannot afford. The job that is available now becomes the job they must take, swapping stethoscopes for steering wheels out of sheer necessity.

Yet, within this challenging reality lies a story of profound resilience. Every fare collected and every box stacked represents a sacrifice made for loved ones. It is a testament to an unwavering commitment to provide, demonstrating that while a profession can be left behind, purpose and dignity are carried with them, no matter the work.

The Void Left Behind: Sri Lanka’s Brain Drain Crisis

While Sri Lankan professionals find new lives abroad, their departure carves a deep and widening void in the nation they left behind. This mass exodus, triggered by economic despair, is not merely a collection of individual choices; it is a national crisis—a hemorrhage of its most vital asset: its human capital. The very people with the skills, experience, and education needed to spearhead a recovery are the ones forced to leave.

The consequences are stark and immediate. Hospitals, already strained by supply shortages, now face critical staff deficits as doctors and nurses seek stability overseas. The engine of innovation sputters as engineers and IT specialists, who once drove a burgeoning tech sector, take their talents elsewhere. University lecture halls lose seasoned academics, diminishing the quality of education for the next generation and severing a link to critical research and development.

This exodus creates a devastating, self-perpetuating cycle. As skilled professionals—often higher-income earners—depart, the nation’s tax base shrinks, further hampering the government’s ability to fund essential services and enact recovery plans. The deteriorating public systems, in turn, push more people to emigrate, deepening the crisis. It is a slow, hollowing-out process that leaves the country poorer in both wealth and expertise.

The true cost is not just measured in numbers but in lost potential. Each departure represents a loss of mentors, leaders, and problem-solvers. For every professional who trades a stethoscope for a steering wheel or a blueprint for a barista apron, Sri Lanka loses more than just a skilled worker; it loses a pillar in its foundation and a crucial piece of its future.

The Financial Paradox: Earning More, Feeling Poorer

On paper, the financial logic for a Sri Lankan professional to downskill abroad seems irrefutable. A former university lecturer now working as a caregiver in Europe might earn a monthly salary that, when converted to Sri Lankan Rupees, equals several months of their previous academic pay. This powerful currency arbitrage allows them to send life-sustaining remittances home, settling debts, funding children’s education, and building a safety net that the collapsing domestic economy dissolved. From afar, they are a success story.

Yet, this numerical success often masks a harsh reality. The high cost of living in their host countries creates a profound disconnect between their earnings and their actual financial well-being. That impressive salary is quickly eroded by exorbitant rent for a small room, steep transportation costs, and grocery bills that would be unthinkable back home. After covering basic necessities, the disposable income left for personal use can be shockingly modest. Many find themselves living more frugally than they ever did as professionals in Sri Lanka, sharing cramped apartments and forgoing simple luxuries they once took for granted.

This paradox extends beyond bank balances. It’s a feeling of diminished purchasing power and social standing. An architect who once designed bespoke homes now finds it impossible to even consider renting a decent apartment for themselves alone. The income that makes them a provider to their family back in Sri Lanka barely keeps them afloat in their new environment. They are caught in a strange duality: financially potent from a distance, yet personally impoverished up close. The sacrifice is clear—they trade their professional identity and a comfortable lifestyle for the ability to provide stability for loved ones, a trade that leaves them feeling both richer and poorer at the same time.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Systemic Barriers to Re-qualification

For many Sri Lankan professionals arriving on foreign shores, the hope of rebuilding their careers quickly dissolves into a disorienting reality. The path to re-qualification is not a straightforward process but a labyrinth of systemic barriers, designed for a different context and seemingly indifferent to the urgency of their situation. What they encounter is a system that often fails to recognize years of hard-earned expertise.

The first and most formidable wall is financial. Licensing exams, credential assessments, and mandatory bridging courses are prohibitively expensive, often costing thousands of dollars—a fortune for those who have left a collapsed economy with limited savings. The process is also excruciatingly slow. A doctor might face years of rigorous exams and a desperate search for a limited number of residency placements. An engineer may find their degree is not fully recognized, forcing them into lengthy and costly supplementary education.

Beyond the cost and time, there is the bureaucratic maze. Navigating the requirements of professional licensing bodies can be a full-time job in itself, filled with confusing paperwork and slow-moving evaluations. This is often compounded by the infamous catch-22 of the job market:

“They tell you that you need local experience to get a professional job, but no one will give you that first opportunity to gain it. You are trapped.”

This relentless cycle is not just a practical hurdle; it is a deeply demoralizing experience that erodes professional identity and self-worth. Faced with these insurmountable obstacles and the pressing need to provide for their families, many have no choice but to abandon their professional aspirations, at least temporarily. The stethoscope is exchanged for a steering wheel, not by choice, but by necessity.

Resilience and the Dream of Return

Beneath the uniform of a delivery driver or the apron of a barista lies the unyielding spirit of a professional who has not surrendered their identity, only adapted their circumstances. For the Sri Lankan doctors, engineers, and lawyers navigating foreign cities in roles far removed from their expertise, resilience is more than mere survival. It is an active, daily choice fueled by a profound sense of responsibility to families back home and a powerful vision for the future.

This resilience manifests in quiet dignity. It is the meticulous care a former architect takes in a warehouse job, or the calm bedside manner a surgeon applies to customer service. They build new communities, sharing stories and support with compatriots on similar paths. They learn to compartmentalise, understanding that their current employment is a tool, not a final definition of their worth. This mental fortitude allows them to hold onto their professional self while performing labour that society may deem unskilled, knowing its true purpose is to secure a lifeline for their loved ones.

What truly sustains them through long shifts and lonely nights is the dream of return. This is not a permanent migration but a strategic, temporary retreat. Every dollar saved is a brick for a future clinic, a seed for a re-established law practice, or capital to rebuild a business in a stabilised Sri Lanka. They envision returning not just with savings, but with new perspectives and a renewed determination to contribute to their nation’s recovery. This dream transforms the mundane into a mission, reframing their journey not as a descent, but as a crucial detour on the long road home.