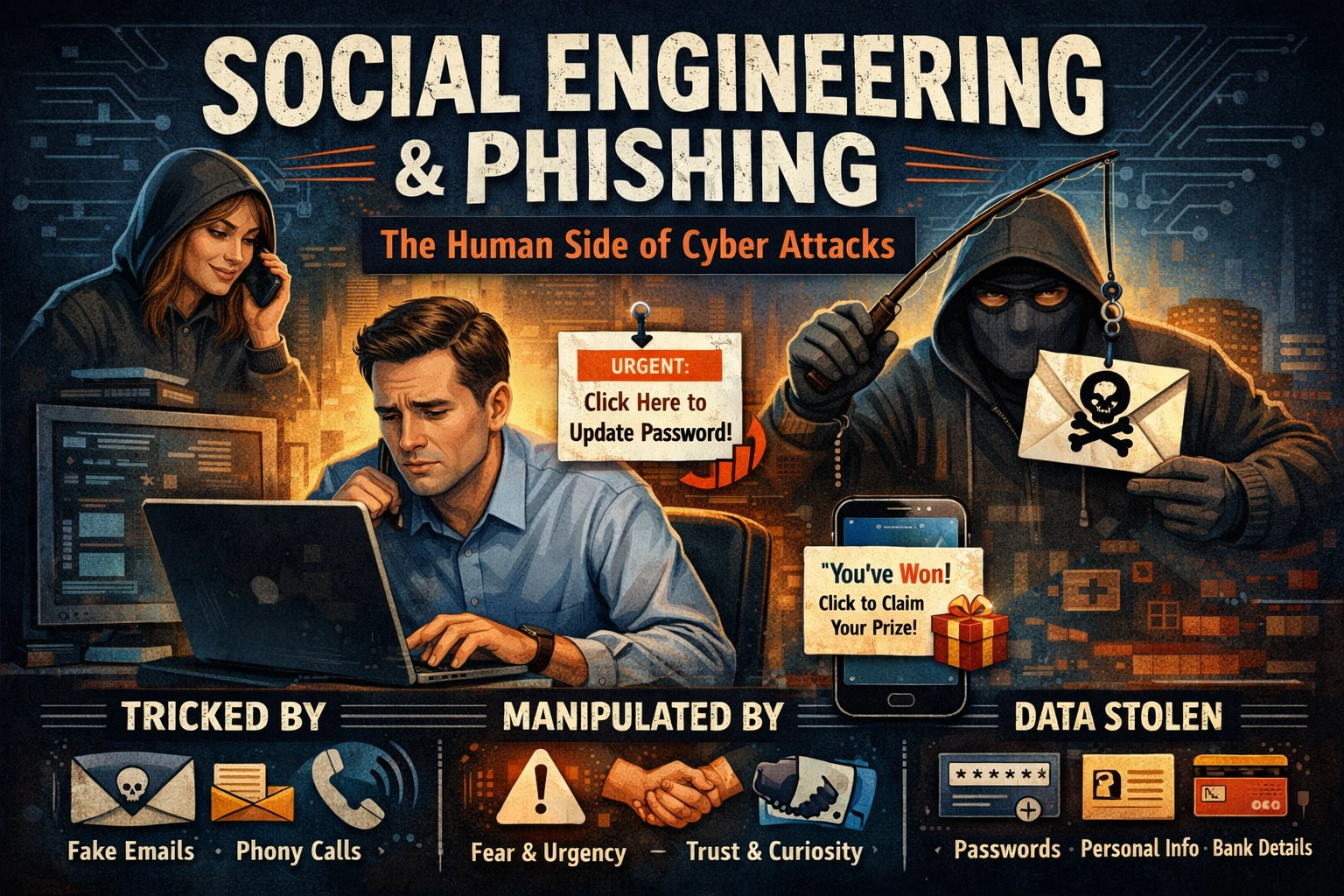

Social Engineering and Phishing: How Cybercriminals Target People, Not Just Systems

Most high‑profile cyber attacks involve a human being tricked into doing something against their own interests—clicking a malicious link, sharing a password, or approving an unusual payment. This is the realm of social engineering, where attackers exploit trust and psychology rather than purely technical vulnerabilities.

Phishing remains the most common and effective social engineering technique, used in everything from basic scams to advanced espionage campaigns.

Common Types of Social Engineering Attacks

Social engineering comes in many forms, often tailored to the victim’s role and organisation.

1. Phishing (email)

Attackers send emails that appear to come from trusted entities—banks, software vendors, internal departments—prompting the recipient to click a link or open an attachment.

Typical objectives:

- Steal credentials via fake login pages.

- Deliver malware or ransomware via attachments.

- Trick users into wiring money or buying gift cards.

2. Spear phishing and whaling

Spear phishing targets specific individuals (e.g., finance or HR staff), often using personal details scraped from social media or company websites. Whaling targets high‑value individuals like CEOs or CFOs, often with carefully crafted messages.

3. Vishing and smishing

- Vishing: Voice phishing via phone calls, impersonating support, banks or even management.

- Smishing: SMS messages with malicious links or urgent requests (“Your parcel is held; click to confirm address”).

These channels bypass email filters and often catch users off guard.

4. Physical social engineering

Attackers may tailgate into offices, pose as delivery personnel, or rely on misplaced USB drives labelled “Payroll” to gain physical access or get malware into networks.

Psychological Techniques Attackers Use

Understanding the psychological levers behind social engineering helps organisations design better training.

Common manipulation techniques:

- Urgency: “Your account will be closed in 2 hours” pushes impulsive actions.

- Authority: Impersonating a manager, CEO or auditor to override doubt.

- Scarcity: “Last chance to secure your bonus” or “limited‑time security update.”

- Reciprocity: Offering help or rewards before asking for information.

- Social proof: “Everyone in your team has already completed this form.”

These methods exploit normal human tendencies rather than technical weaknesses.

Building a Culture That Resists Social Engineering

Technology alone cannot stop social engineering; organisations need cultural and process defences.

Key elements:

- Clear processes: For payments, data access requests and password resets, so staff know what “normal” looks like.

- Empowered scepticism: Encourage employees to question unexpected requests—even from senior staff—and verify via a second channel.

- Non‑punitive reporting: Staff should feel safe reporting suspicious messages or admitting mistakes quickly.

When people are punished harshly for errors, they are more likely to hide incidents, allowing attackers more time inside.

Practical Defences and Training Approaches

Effective anti‑phishing programs combine training, testing and technical controls.

Training content

Focus on:

- Recognising tell‑tale signs: mismatched domains, badly written messages, unusual tone.

- Checking URLs before clicking, especially for login pages and payment portals.

- Verifying invoices or payment changes via phone or internal chat, not just email.

Short micro‑training modules or monthly “scam of the month” examples keep awareness fresh.

Testing and reinforcement

Simulated phishing campaigns can measure susceptibility and guide targeted training. Results should be used to educate, not shame.

Technical Controls That Support Humans

While social engineering targets people, technical tools can reduce risk.

Helpful controls:

- Email filtering and sandboxing for attachments.

- Multi‑factor authentication, to limit damage if credentials are stolen.

- Domain‑based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance (DMARC) to reduce spoofed emails.

- Browser isolation and URL rewriting to detect malicious links.

These protections act as safety nets when someone does click.

Responding to a Successful Social Engineering Attack

If an employee falls victim, rapid response limits damage.

Immediate steps:

- Reset compromised passwords and revoke tokens.

- Isolate affected devices for malware scans.

- Notify internal teams and, if required, customers or partners.

- Review logs for further suspicious activity.

Post‑incident reviews should focus on improving processes and training, not assigning blame.