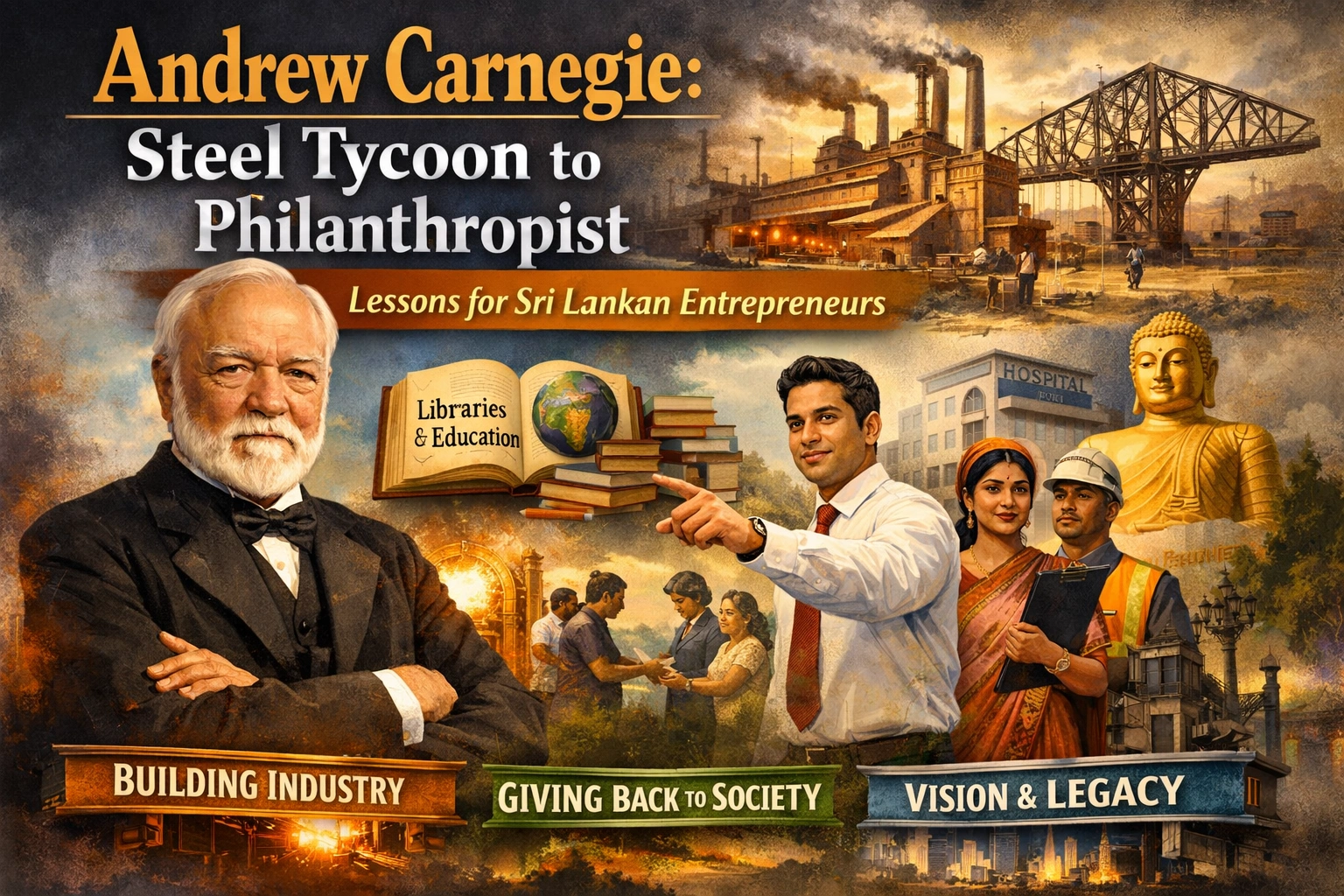

Introduction

In the annals of global entrepreneurship, Andrew Carnegie stands as a towering figure—a Scottish immigrant who rose from poverty to become the richest man in the world through steel innovation, only to give away nearly his entire fortune. Born in 1835, Carnegie’s life exemplifies the power of grit, strategic vision, and ethical wealth redistribution, principles that resonate deeply with Sri Lankan entrepreneurs navigating a post-colonial economy blending tea plantations, apparel exports, and emerging tech hubs like Colombo’s IT parks. For Sri Lankans, whose nation has produced business icons like the late Deshamanya A.Y.C. Mohamed in retail and modern disruptors in fintech, Carnegie’s story offers timeless lessons in scaling industries amid challenges like labor strikes and global competition, much like Sri Lanka’s garment sector evolution.

Early Life and Background

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, to a poor weaver father, William Carnegie, and mother Margaret Morrison, in a one-room cottage that today serves as a museum. The family’s handloom business collapsed due to mechanized factories, mirroring disruptions Sri Lankan handloom weavers faced during British colonial industrialization in the 19th century. In 1848, at age 13, the Carnegies immigrated to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, fleeing poverty—a journey akin to economic migrations from rural Sri Lanka to urban Colombo or Middle Eastern opportunities today.

Carnegie’s formal education ended at age 15, but a pivotal encounter shaped him: Colonel James Anderson opened his personal library to working boys, igniting Carnegie’s lifelong love for reading. This self-education propelled him from a bobbin boy in a cotton factory earning $1.20 weekly to telegraph messenger. In Sri Lanka, similar tales abound, such as entrepreneurs from Jaffna’s modest beginnings who bootstrapped tech startups, underscoring how access to knowledge—via institutions like the British Council libraries in Kandy or the National Library in Colombo—fuels ambition.

Rise in Business and Key Ventures

Carnegie’s career ignited at the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1853 as a telegraph operator, rising to superintendent by 1860 under mentors Thomas A. Scott and J. Edgar Thomson. He astutely invested earnings in ventures like the Woodruff Sleeping Car Company, introducing the first successful sleeping cars on U.S. rails—a innovation parallel to Sri Lanka’s Ceylon Government Railway expansions in the 1860s that spurred trade in tea and rubber from hill country estates.[3][4]

By 1865, at age 30, Carnegie quit the railroad with an annual income of $50,000 from investments in oil fields, bridges, and iron mills. He founded Keystone Bridge Company, capitalizing on post-Civil War infrastructure booms. His masterstroke came in steel: adopting the Bessemer process in 1875 at Homestead Steel Works near Pittsburgh, he slashed costs and scaled production. By 1889, holdings consolidated into Carnegie Steel Company dominated U.S. output, surpassing Britain’s—a feat echoing how Sri Lanka overtook competitors in apparel, exporting $5.4 billion in 2023 via efficiency and vertical integration in factories around Katunayake.[1][2][3]

Key strategies included vertical integration—controlling mines, ships, and railroads—and relentless cost-cutting, amassing a fortune through calculated risks. In 1901, he sold to J.P. Morgan for $480 million (equivalent to $16 billion today), forming U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation. Sri Lankan business leaders like those at Hayleys PLC, with diversified ventures from tea to logistics, can draw parallels in building resilient supply chains amid global volatility.[4][5]

Major Achievements and Innovations

Carnegie’s innovations revolutionized steel: the Bessemer converter enabled mass production of cheap, high-quality steel for rails, bridges, and skyscrapers, fueling America’s Gilded Age. By 1900, Carnegie Steel produced more metal than all of Britain, with $40 million profits that year alone—his share $25 million.[2][3] He pioneered management practices like employee profit-sharing and safety improvements, though not without controversy.

His Homestead plant became a symbol of industrial might, much like Sri Lanka’s Vallibel One’s manufacturing hubs driving GDP contributions of 25% from industry. Carnegie’s wealth peaked at $380 million upon retirement, making him richer than Rockefeller temporarily. These milestones highlight entrepreneurial foresight, relevant to Sri Lanka’s push for value-added steel production via Liberty Steel’s investments in Horana, aiming to reduce imports and boost exports.[1][4]

Innovations in Efficiency

Beyond Bessemer, Carnegie adopted open-hearth furnaces for superior steel and integrated operations to eliminate waste, dropping rail prices from $100 to $20 per ton. Such efficiencies inspire Sri Lanka’s renewable energy innovators at Access Engineering, optimizing solar farms in the Dry Zone for cost-effective power.[3][5]

Philanthropy and Social Impact

Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth” essay (1889) argued the rich must administer surplus wealth for societal good, not hoard it—a philosophy aligning with Sri Lankan Buddhist principles of dana (generosity) seen in philanthropists funding temples in Anuradhapura or schools in Galle. He donated $350 million lifetime, building 2,510 libraries worldwide, including in Colombo’s public access points today.[1][2]

Foundations include Carnegie Mellon University (1900, from Technical Schools), Carnegie Hero Fund (1904) rewarding everyday heroes, and Carnegie Corporation (1911) supporting education. In Sri Lanka, where literacy rose from 88% to 92% via public libraries (per UNESCO 2023), Carnegie’s model influences initiatives like the Hayleys Foundation’s literacy programs in rural Sabaragamuwa. His giving aimed to uplift the working class, countering industrial inequities much like Sri Lanka’s Samurdhi program aids 1.5 million families.[2][7]

Personal Life and Character

Carnegie was frugal yet ambitious, a voracious reader with a Scottish brogue, valuing family above fame. He married Louise Whitfield in 1887 at 51, fathering daughter Margaret; they resided in opulent Skibo Castle, Scotland, but he lived modestly in New York. Mentors like Scott shaped his ethics, blending Presbyterian work ethic with free-market belief.

Controversies shadowed him: the 1892 Homestead Strike saw 10 deaths amid clashes with Pinkerton agents hired by partner Henry Clay Frick, drawing criticism for ruthless tactics—echoing Sri Lanka’s 1980s garment strikes resolved through tripartite dialogues. Yet, his profit-sharing and libraries balanced this duality, teaching entrepreneurs ethical navigation of labor tensions in places like Sri Lanka’s Free Trade Zones.[1][3][4]

Legacy and Historical Significance

Today, historians view Carnegie ambivalently: a capitalist titan whose steel built modern America, yet whose methods exacerbated inequality. His philanthropy endures via 22 organizations impacting millions, influencing figures like Bill Gates’ Giving Pledge. For Sri Lankan entrepreneurs in Colombo’s startup ecosystem—home to 500+ ventures per 2024 SLASSCOM data—lessons abound: innovate boldly (like Carnegie’s Bessemer), scale vertically (as MAS Holdings does in apparel), and give back philanthropically, as seen in Dialog Axiata’s digital inclusion drives reaching 20 million users.

Carnegie’s immigrant success story inspires Sri Lanka’s diaspora returnees fueling tourism in Ella or e-commerce in Batticaloa. He died penniless in 1919, fulfilling his vow, leaving a blueprint for sustainable entrepreneurship amid global challenges like climate-impacted tea yields (down 10% in 2023 per Ceylon Tea Board). In Sri Lanka’s “Entrepreneurship” landscape, Carnegie’s life urges blending profit with purpose for national progress.

(Word count: 1028)