If you have checked the price of diapers, daycare, or hockey equipment lately, you already know the sinking feeling. Raising a child in Canada isn’t just an emotional commitment; it is a massive financial undertaking. Recent estimates suggest the cost of raising a child to age 17 can easily exceed $300,000, and that is before you even think about university tuition or a down payment on their first home. It’s enough to make any parent stare at their bank account in mild panic.

But here is the good news: the Canadian tax system is surprisingly designed to help you shoulder that load, provided you know exactly where to look. There are thousands of dollars sitting on the table—tax-free cash and deductions—that many families miss simply because the rules feel dense or obscure. I have seen smart, organized parents leave significant money behind because they assumed they made “too much” to qualify or didn’t realize a specific camp receipt was a write-off.

You work hard for your family. The goal here isn’t to turn you into a tax accountant, but to hand you the keys to the benefits you are legally entitled to claim. Let’s look at how to get that money back into your pocket where it belongs.

The Heavy Lifter: Maximizing the Canada Child Benefit (CCB)

If there is one pillar of Canadian family finance you need to understand inside and out, it is the Canada Child Benefit (CCB). This isn’t just a tax credit; it is a tax-free monthly payment that hits your bank account to help with the cost of raising children under 18. Because it is tax-free, it doesn’t increase your taxable income. It is pure spending power.

The government calculates this benefit based on your Adjusted Family Net Income (AFNI). Think of it as a sliding scale: the less you make, the more you get. However, a common misconception I hear from higher-earning professionals is, “I probably won’t qualify, so why bother?” This is a mistake. The income thresholds are higher than you might think, especially if you have more than one child.

The “July Surprise”

The CCB operates on a benefit year that runs from July to June. This timing often catches parents off guard. Your payments starting in July 2024, for example, are based on the tax return you filed for the 2023 income year. This lag is why filing your taxes on time is non-negotiable, even if you had zero income. If you or your spouse fail to file, the payments stop dead in July.

I recall a client, let’s call him David, who was a stay-at-home dad with no income for a year while his wife worked. He didn’t think he needed to file a return. Come July, their $600 monthly check vanished. We had to file his late return to reinstate it, but they went three months without that cash flow during a tight summer. Don’t let that be you.

The Shared Custody Nuance

Family dynamics have shifted, and the CRA has adapted—though the paperwork can be tricky. If you share custody of a child roughly 50/50, you don’t just split the check. The CRA considers you to be in a “shared eligibility” situation. In this case, each parent gets 50% of what they would have received if they had full custody, based on their own specific income.

This distinction matters because if you earn significantly less than your ex-spouse, your 50% share might be quite substantial, whereas theirs might be minimal. You must apply for this status; don’t assume the CRA knows your custody schedule just because you got divorced.

Strategic Deductions: The Child Care Expense Rules

While the CCB puts cash in your account, the Child Care Expense Deduction (CCED) keeps cash from leaving it in the form of income tax. This is a deduction, not a credit. It lowers your taxable income, which saves you money at your marginal tax rate. For high earners, this is incredibly powerful.

You can generally deduct up to $8,000 per child under age 7, and $5,000 per child aged 7 to 16. If you have a child with a disability, that limit jumps to $11,000. But there is a strict rule that trips up many families: the lower-income spouse must claim the deduction.

Why the “Lower Income” Rule Exists

The CRA isn’t trying to be difficult; they are trying to prevent the highest earner (who pays the highest tax rate) from getting a massive tax break. By forcing the lower earner to claim the deduction, the government limits the tax revenue loss.

Here is a practical example: Imagine Sarah earns $120,000 and Mark earns $40,000. They spend $15,000 on daycare for their two toddlers. Sarah wants to claim that $15,000 because at her tax bracket, the refund would be huge. But she can’t. Mark has to claim it. Since Mark is in a lower tax bracket, the refund is smaller than it would be for Sarah, but it still reduces his tax bill significantly—potentially to zero.

There are exceptions, of course. If the lower-income spouse was in school, in prison, or hospitalized for a long period, the higher earner might be able to claim a portion. If you fall into one of those specific buckets, look at Part C of Form T778 very carefully.

What Actually Counts?

You probably know daycare counts. But did you know that day camps and overnight sports camps often count too? If the primary goal of the camp is childcare (allowing you to work), it is usually eligible. However, if you are paying for an elite hockey academy where the goal is education or training rather than supervision, the CRA might push back. Keep your receipts, and make sure the provider’s Social Insurance Number (or business number) is on them. The CRA loves to audit this specific deduction.

The “Hidden” Credits: Disability and Single Parents

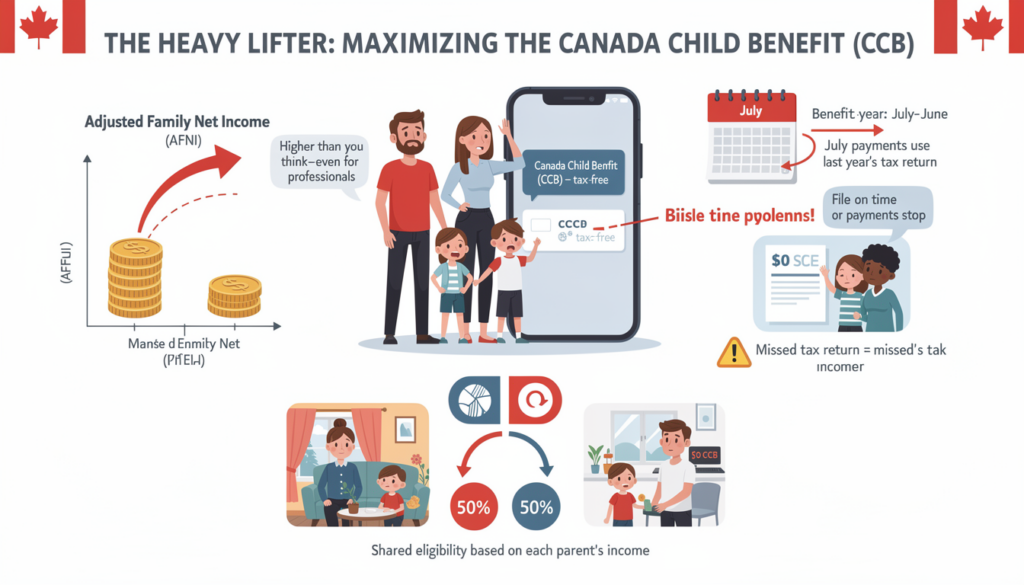

Some of the most valuable credits are the ones people assume don’t apply to them. The Child Disability Benefit (CDB) and the Eligible Dependent Amount are two areas where I consistently see families leaving thousands of dollars unclaimed.

The Child Disability Benefit (CDB)

When people hear “disability,” they often think of visible physical limitations. However, the CRA’s definition includes severe and prolonged impairment in mental functions, which can include autism spectrum disorder (ASD), severe ADHD, and other cognitive or developmental delays. If your doctor certifies that your child has marked restrictions in daily living activities, you may qualify for the Disability Tax Credit (DTC).

Once you are approved for the DTC (Form T2201), the Child Disability Benefit kicks in automatically as a supplement to your CCB. We are talking about up to $3,322 extra per year (indexed annually). The real magic? It is often retroactive. I once helped a family whose son had been diagnosed with severe autism five years prior. We applied, got approved, and the CRA issued a lump sum payment for the previous years that totaled over $15,000. If you suspect your child qualifies, talk to your pediatrician immediately.

The Eligible Dependent Amount

If you are a single parent and you are not claiming a spouse on your taxes, you have a golden ticket called the “Amount for an Eligible Dependent.” In tax slang, we often call this the “equivalent-to-spouse” credit.

Basically, the government allows you to treat one child as a dependent adult for tax purposes. This gives you a massive tax credit roughly equal to the basic personal amount (around $15,000). This can result in $2,000 to $3,000 in actual tax savings. The catch? You can only claim it for one child, and you generally cannot claim it if you are living with a partner who supports the child. But for a newly divorced or single parent, this is often the difference between owing taxes and getting a refund.

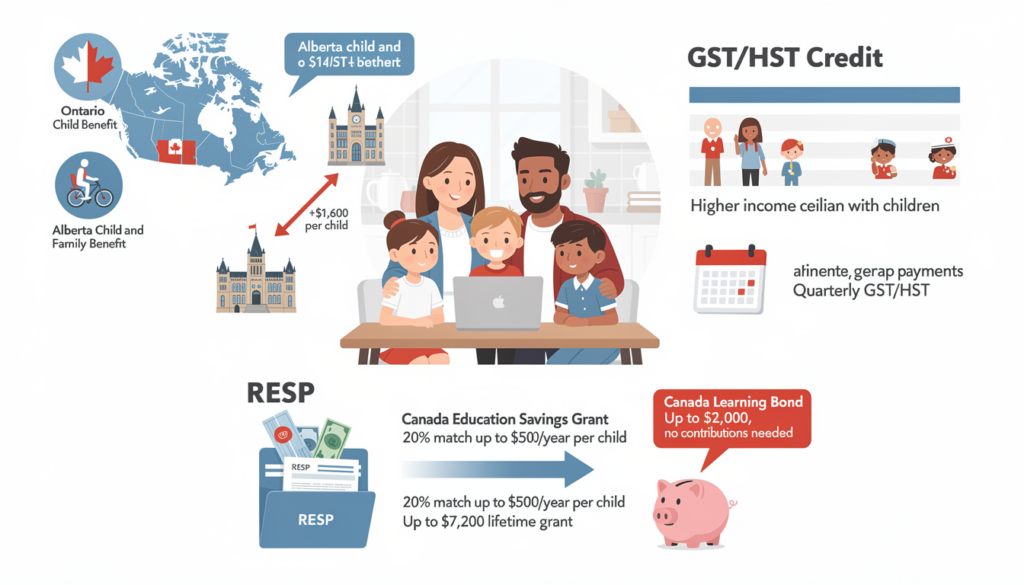

Provincial Top-Ups and the GST/HST Credit

Federal benefits are the main course, but provincial credits are the dessert—and sometimes the dessert is substantial. Most provinces have their own version of the child benefit that stacks on top of the federal CCB. These are usually combined into a single monthly payment, so you might not even realize you are getting two different benefits.

For instance, the Ontario Child Benefit (OCB) can add roughly $1,600 per child annually for low-to-moderate-income families. Alberta has the Alberta Child and Family Benefit (ACFB). These programs usually have different income phase-out thresholds than the federal ones.

The GST/HST Credit

You might remember getting GST cheques when you were a low-income student. As your income grew, those likely stopped. But here is the twist: having children raises the income ceiling for eligibility. A couple with three kids can earn significantly more than a single person and still qualify for GST/HST quarterly payments.

You don’t need to apply separately for these. When you file your taxes and list your dependents, the CRA’s computer does the math. This reinforces my earlier point: even if your teenagers have part-time jobs and you think your household income is “too high,” file everyone’s return. You might be surprised to find a few hundred dollars landing in your account every quarter just for being a family unit.

Free Money for the Future: The RESP

While this technically isn’t a “tax credit” you claim on your return, ignoring the Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP) is like walking past a $500 bill on the sidewalk every year. The Canada Education Savings Grant (CESG) is a direct 20% match on the first $2,500 you contribute annually per child.

You put in $2,500; the government drops in $500. It is an immediate 20% return on investment before you even invest the funds in the market. The lifetime limit per child is $7,200 in grant money.

The “Catch-Up” Strategy Life gets messy. Maybe you couldn’t afford to contribute for a few years when the kids were babies. That is fine. The system allows you to carry forward unused grant room. You can catch up on one previous year at a time. So, if you have a 10-year-old and you have never contributed, you can put in $5,000 this year and get $1,000 in grants (covering the current year and one past year). You can’t do it all at once, but with strategic planning over a few years, you can claw back all that free money.

For lower-income families, the Canada Learning Bond (CLB) is even better. It puts money into an RESP (up to $2,000) without you having to contribute a single cent of your own money. You just have to open the account. If you know a family struggling to make ends meet, tell them about the CLB—it is literally free money for their child’s future education.

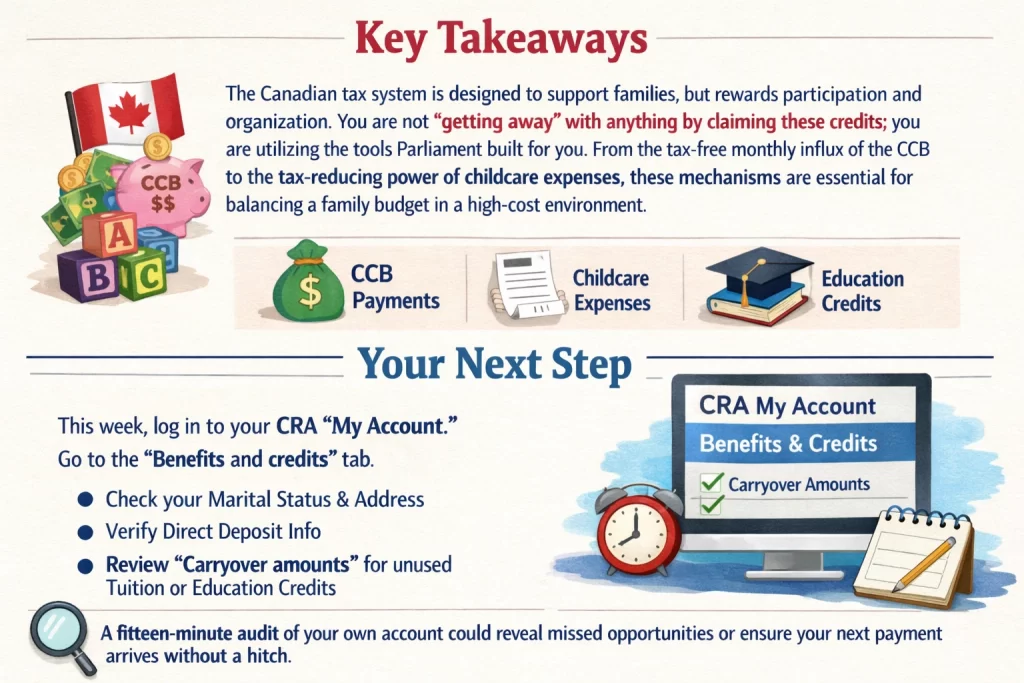

Key Takeaways

The Canadian tax system is designed to support families, but it rewards participation and organization. You are not “getting away” with anything by claiming these credits; you are utilizing the tools Parliament built for you. From the tax-free monthly influx of the CCB to the tax-reducing power of childcare expenses, these mechanisms are essential for balancing a family budget in a high-cost environment.

Your Next Step: This week, log in to your CRA “My Account.” Go to the “Benefits and credits” tab. Check to see if your marital status, address, and direct deposit information are current. Then, look at your “Carryover amounts” to see if you have unused tuition or education credits from your own past that you might have forgotten. A fifteen-minute audit of your own account could reveal missed opportunities or ensure your next payment arrives without a hitch.