If you’ve ever wondered why British students take GCSEs at 16 while their American counterparts sit for SATs, you’ve spotted one of the education system’s defining features: structure. The British school system isn’t just different—it’s deliberately designed around clear progression points, each with specific outcomes. Most parents and students navigating this system discover that understanding these stages transforms decision-making, from choosing secondary schools to planning university applications.

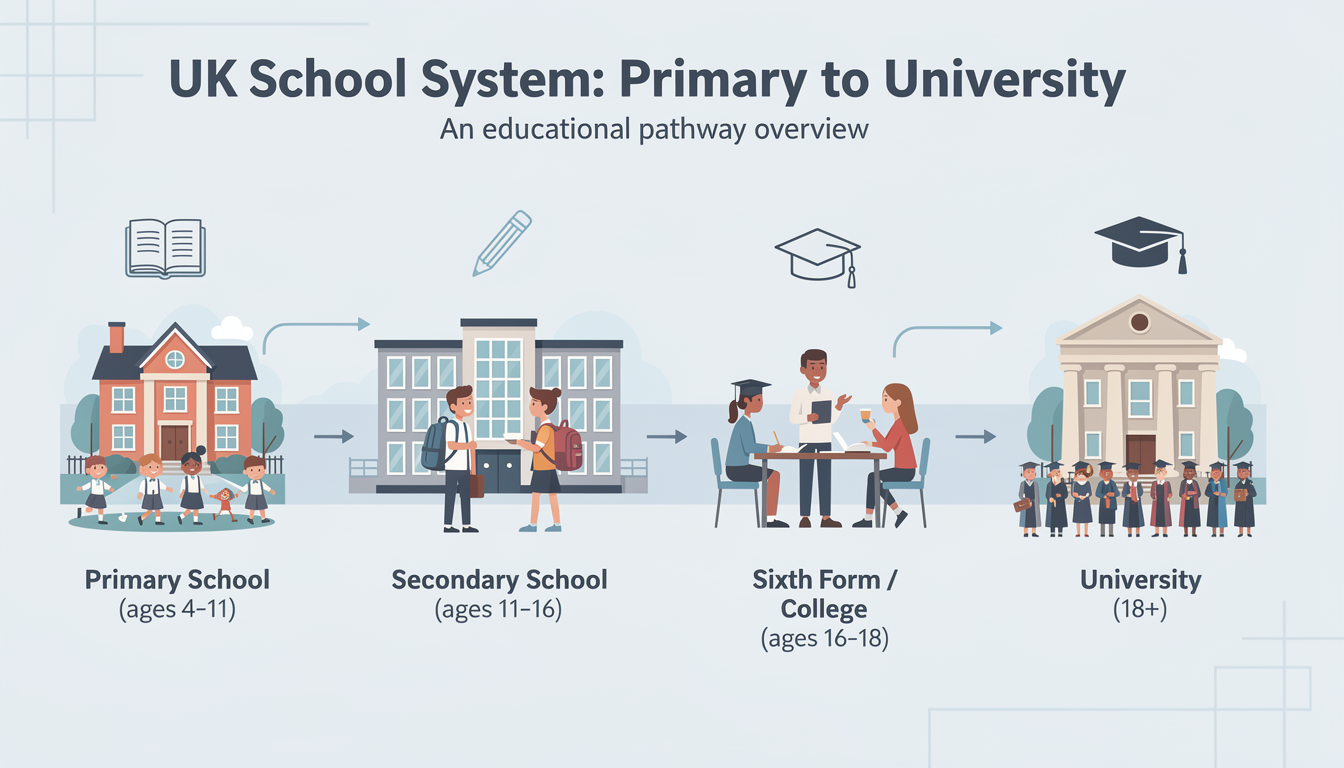

The journey from primary school through university follows a remarkably consistent framework. Primary education (ages 5-11) builds foundational skills across English, mathematics, and science. Secondary education (ages 11-16) culminates in GCSEs—standardized exams that genuinely shape your next steps. Then comes the decision point: A-Levels, vocational routes, or apprenticeships. This article breaks down each stage with practical insights about what actually happens in classrooms, how selection works, and which choices lead where.

You’ll learn the real differences between grammar schools and comprehensives, what university admissions officers actually look for, and how to position yourself or your child for success at each transition point. Whether you’re relocating to the UK, supporting a student through these systems, or simply curious about how British education works, this guide provides the specific details that matter.

Overview of the British Education System

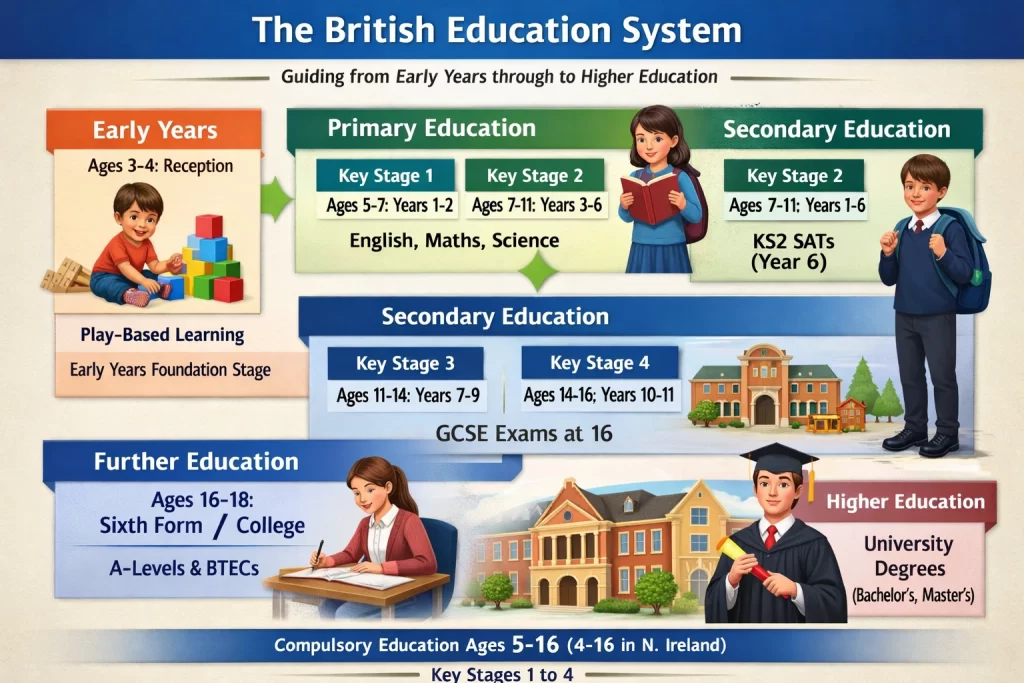

You start with early years, then move through primary, secondary, further education, and higher education. These four main levels guide students from play-based learning to advanced degrees[1][2]. Compulsory schooling runs from age 5 to 16 (age 4 in Northern Ireland), split into Key Stages 1 through 4[1][2][7].

Picture a child like young Alex entering Reception at age 4. Teachers focus on play to build social skills and basics through the Early Years Foundation Stage. By age 5, Alex hits Key Stage 1 (ages 5-7, Years 1-2). Here, you tackle core subjects: English, maths, science. A phonics screening check at Year 1 end spots reading gaps early. Parents track progress via teacher assessments[3].

Key Stage 2 (ages 7-11, Years 3-6) deepens those skills. Students face KS2 SATs in Year 6—tests in English, maths, science that measure readiness for secondary school. Alex aces maths but needs reading support; teachers craft targeted plans[3]. At 11, everyone shifts to secondary: Key Stage 3 (ages 11-14, Years 7-9) broadens subjects like computing, languages, art. No national tests, but internal progress checks keep you on track[3].

Key Stage 4 (ages 14-16, Years 10-11) ramps up. You pick GCSE subjects—say, 8-10 including must-haves like English, maths, science. GCSE exams at 16 decide next steps: pass well (grades 9-4), and doors open to further education[1][3][4]. Compulsory ends here, but most continue.

Further education (ages 16-18, Key Stage 5) means sixth form or college. Choose 3-4 A-Levels, like biology, chemistry, physics for medicine aspirants, or BTECs for hands-on trades. Strong GCSEs (at least 5s in key subjects) get you in. From there, higher education beckons: three-year bachelor’s degrees, where you specialize fast[2].

Exceptions exist—Scotland tweaks ages, academies flex slightly until 2026 reforms align everyone[5]. Track your child’s stage via school reports; prep for SATs with daily reading, GCSEs through past papers. This path builds skills step by step[1][2][3].

Primary Education: Building Foundations (Ages 5-11)

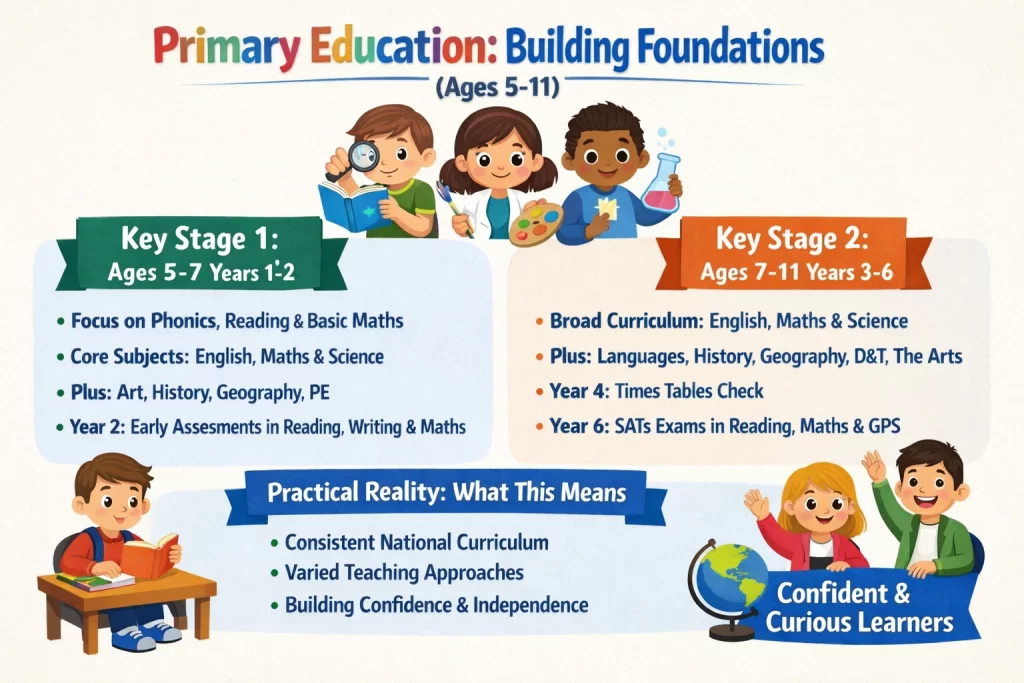

This brings us to something often overlooked: primary school isn’t just about teaching children to read and do sums. It’s the critical window where foundational habits, curiosity, and confidence take root. In England, primary education spans two Key Stages, each with distinct learning objectives and assessment points that shape how schools structure their approach.

Key Stage 1: Years 1-2 (Ages 5-7)

When children enter Year 1 at age five, they encounter the first formal stage of compulsory education. The focus here is deliberately narrow and intentional. English, maths, and science form the core subjects, supported by design and technology, history, geography, art and design, music, and physical education[4][8]. Schools also provide religious education and relationships and health education.

A Year 1 teacher might spend considerable time on phonics—not randomly, but following the phonics screening check that happens in Year 1. By Year 2, children sit optional tests in English reading, grammar, punctuation, spelling, and maths, alongside teacher assessments in science and writing. This dual-assessment approach gives parents and educators a fuller picture than standardized tests alone.

Key Stage 2: Years 3-6 (Ages 7-11)

As children progress into Key Stage 2, the curriculum expands significantly. The core subjects remain—English, maths, and science—but now students engage with ancient and modern foreign languages, design and technology, history, geography, and the arts[1][4]. Schools often weave in citizenship and personal, social, and health education informally.

Year 6 marks the end of primary school with Standard Assessment Tests (SATs). These national tests in English reading, maths, and grammar, punctuation, and spelling provide a standardized measure before transition to secondary school. Many schools use Year 4’s times tables check as an early indicator of mathematical fluency.

Practical Reality: What This Means

Whether your child attends a state-funded or private primary school, the national curriculum ensures a consistent baseline across subjects and standards[1]. Schools have flexibility in how they teach content, which explains why two Year 3 classes might approach history differently—one through project-based learning, another through traditional lessons.

The real value of primary education lies in building confident learners who can read, reason, and work collaboratively. By age eleven, students should have developed genuine independence in their thinking, not just mastered curriculum content.

Secondary Education: Key Stages 3 and 4 (Ages 11-16)

And this is where things get practical. You’ve guided your child through primary school. Now, in secondary education, they tackle real skills that shape their future. Key Stage 3 (Years 7-9, ages 11-14) throws them into a broad curriculum. They study English, maths, science, history, geography, modern foreign languages, design and technology, art and design, music, physical education, citizenship, and computing. Schools also deliver relationships and health education, sex education, and religious education.[3][1] This mix builds confidence. Students explore interests before narrowing down.

Picture Sarah, starting Year 7. She struggled with French pronunciation. Her teacher used daily speaking drills—simple phrases first, then debates. By Year 9, Sarah led class discussions fluently. That’s Key Stage 3 in action: teachers spot weaknesses early and fix them through targeted practice. Schools often group students by attainment in maths or languages, mixing others for form classes.[7][1] You can help at home. Review homework weekly. Ask about history timelines or geography maps. Tie it to family trips—discuss UK landscapes after a Lake District visit.

Key Stage 4 (Years 10-11, ages 14-16) ramps up. Compulsory education ends here, but most aim for GCSEs—typically 9-12 subjects. Core ones stay: English, maths, science. Add computing, physical education, citizenship. Schools offer at least one from arts, design and technology, humanities, modern foreign languages.[3][2] Depth increases. English covers prose, poetry, spoken language. Maths hits algebra, geometry, statistics. Science demands experiments and analysis across biology, chemistry, physics.[1]

Prep for GCSEs starts in Year 9 options evening. Students pick subjects like triple science or history alongside cores. I remember advising a family: their son, Tom, loved gaming. He chose computing GCSE. We mapped a study plan—past papers twice weekly, flashcards for code syntax. Year 11 mock results jumped two grades. GCSEs open doors to A-levels, apprenticeships, or jobs. Strong grades (7-9, old A/A*) mean more choices post-16.[2][9]

Exceptions exist. Some schools start GCSEs in Year 9. Vocational paths like Technical Awards suit hands-on learners.[3][7] Track progress with parent evenings and reports. Encourage revision routines: 45-minute sessions, breaks, active recall. By Year 11, your child emerges ready for sixth form or college. This stage demands focus. Guide them, and they thrive.

Post-16 Further Education: A-Levels and Alternatives

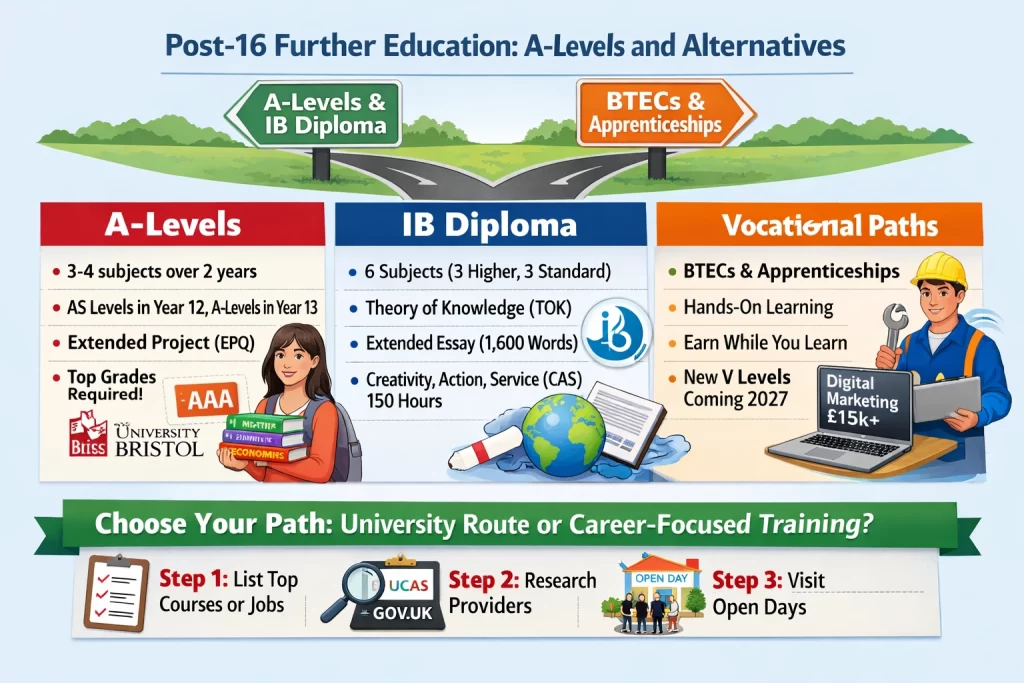

But wait — there’s more to consider. After GCSEs, you face a fork in the road: stick with academic routes like A-Levels or the IB Diploma, or pivot to vocational options such as BTECs, apprenticeships, and emerging qualifications that build hands-on skills for university or jobs[3][7]. Pick based on your strengths—do you thrive in deep subject dives, or prefer applying knowledge right away?

A-Levels remain the go-to for university-bound students. You study 3-4 subjects over two years, focusing intensely on each to hit top grades like A or A, which unis demand for competitive courses[3][4]. In year 12, tackle AS-level assessments; year 13 ramps up to full A-Level exams. I once guided a student, Sarah, who dropped Physics after mocks but aced Maths, Economics, and History. She mixed in an Extended Project Qualification (EPQ)—a 5,000-word independent research piece that unis love as it shows real initiative[3]. This combo landed her at Bristol University for economics. Pro tip: check UCAS tariff points early; three As equal 168 points, beating many alternatives.

IB Diploma: Broader but Rigorous

The International Baccalaureate Diploma offers balance with six subjects—three at higher level, three standard—plus core elements like Theory of Knowledge (TOK), where you debate “How do we know what we know?” and write a 1,600-word essay[3]. Creativity, Action, Service (CAS) logs 150 hours of extracurriculars, building your personal statement. It’s ideal if you want global recognition; many top unis equate 38-45 points to AAA at A-Level. Drawback? Heavier workload—expect 10 subjects effectively. A client of mine switched from A-Levels mid-year to IB at an international school; her TOK reflections turned a good application into an Oxford offer.

Vocational Paths: Skills First

Skip pure academics with BTECs or apprenticeships for technical edge[7]. BTECs (like Extended Diploma in Engineering) mimic A-Levels in UCAS points but emphasize coursework and projects—perfect for portfolios. Apprenticeships blend paid work (e.g., Level 3 in digital marketing, earning £15k+ yearly) with study, no tuition fees[7]. Watch for 2027’s V Levels, a new Level 3 option replacing many vocational quals, mixable with A-Levels for hybrid programmes[1][4][5]. Level 2 pathways like Occupational (job-ready training) suit those resitting GCSEs[4].

Step 1: List top uni courses or jobs. Step 2: Match to providers via UCAS or gov.uk finders. Step 3: Visit open days—ask about work experience hours, mandatory for tech programmes[3]. Exceptions apply for SEND students, with tailored plans. You control this next move; align it with your real goals.

University Education: Higher Degrees and Pathways

You finish A-Levels and aim straight for a bachelor’s degree. These programs run three years full-time, delivering a Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Science (BSc), or similar, with honours as the standard award.[1][7] Expect deep specialization from day one—no broad exploration like in the US. You pick computer science at Manchester, say, and dive into algorithms immediately.[3]

Apply through UCAS. Register online by mid-October for Oxbridge or medicine; everyone else hits the January deadline. List five choices, write a 4,000-character personal statement showcasing your passion—think “I coded my first app at 16 using Python, tackling real data privacy issues.” Universities weigh A-Level grades heavily: AAA for top spots like Imperial, BBB for others. International students swap in equivalents like IB 36 points, plus English tests.[3][1] Interviews probe your fit; medicine demands BMAT scores.[3]

Take Sarah, a straight-A student from a state school. She targeted economics at LSE via UCAS, highlighting her stock market simulations in her statement. Despite competition, her predicted A*AA secured an offer. She started in September, balancing lectures and seminars, graduating with a first-class honours after three years—straight to a City analyst role.[3]

Postgraduates build on that. Master’s degrees pack one year: MSc in data science at Edinburgh, blending coursework and a dissertation. PhDs span three to four years, research-heavy after a master’s or integrated from undergrad in STEM fields like engineering’s MEng (four years total).[1][2][7] Integrated paths suit medicine or architecture too. You propose a research idea for PhDs via university portals, often needing a supervisor first.

Plan ahead. Check UCAS deadlines yearly—they shift slightly. For STEM, seek integrated master’s if industry placements appeal; many add a paid year. Funding? Loans cover UK students up to £9,535 yearly, plus grants for low-income. Internationals tap scholarships like Chevening. Exceptions pop up: part-time options stretch timelines, foundation years bridge gaps for non-traditional paths.[1][2] You control the pace. Match your goals, apply sharp, and land where you thrive.

Plan Your Path Forward

Picture Sarah, a 14-year-old from abroad, who mapped her GCSE choices early, aced her exams, and landed a top university spot—her family credits aligning subjects with career goals from primary onward. You hold that same power: start by listing your child’s strengths now, match them to Key Stage milestones like Year 6 SATs or Year 11 GCSEs, then scout A-Level options that open university doors. Review school reports quarterly, chat with teachers for personalized tweaks, and track progress against national benchmarks. Parents like you turn structure into success by acting early. Download our free UK education timeline PDF to map your study journey and take charge today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What age does compulsory education start in the UK?

Compulsory education begins at age 5 (or 4 in Northern Ireland) and lasts until 16[1][2]

What are GCSEs in the British system?

GCSEs are exams taken at age 16 after Key Stage 4, covering 9-12 subjects[2][3]

How long is a typical UK bachelor’s degree?

Most bachelor’s degrees last 3 years, with 4-year integrated master’s in some fields[7]

What is the difference between primary and secondary education?

Primary covers ages 5-11 (Key Stages 1-2); secondary ages 11-16 (Key Stages 3-4)[1][4]

What follows GCSEs in the UK school system?

Post-16 options include A-Levels, IB, or vocational courses for university or work[3][4]